The need to dispose of viable COVID-19 vaccine is repugnant. Of course, it is easy to understand why this occurs, even when all participants in the system are behaving with the best of intentions. The vaccines have expiry dates and complex handling requirements. Some patients fail to show up for their appointments. Yet an understandable situation is not a tolerable one. More than that, we have a moral imperative to explore every means to avoid vaccine waste.

There are two parts to this problem. The first is logistical. There is, of course, an orderly vaccination process, with rational prioritisation of vulnerable groups, and integration with other healthcare workflows. The early effectiveness of this system in distributing and using vaccine is a point of considerable national pride. There is no need to reinvent the core distribution system.

The early effectiveness of distributing vaccine is a point of considerable national pride. There is no need to reinvent the core distribution system.

What is needed is a more agile secondary system, which can pick up the slack when the main system throws up short-term vaccine surpluses. Sometimes this may be as simple as a rural vaccination centre realising at 3pm that it has one extra five-dose vial of the Pfizer vaccine that expires at the end of the day, and nobody remaining in their priority group to whom to give it. Five doses is insignificant in the scheme of the main distribution scheme – it barely warrants thinking about. For a rural village in an area with a high rate of infection, five doses today rather than next week is significant.

If the hypothetical rural vaccination centre is a surgery, it would be possible for them to search their records for the unvaccinated, and call them to ask them to attend and short notice. Yet the period of time that it would take to identify, call, and explain the situation to potential recipients is non-trivial. In a 3pm-5pm window, it may be possible to raise the interest of one or two people through cold-calling. And that’s only where the vaccination centre is a surgery, with clerical staff, and local patient lists. For non-traditional vaccination sites – shopping centres and stadiums – this option does not exist.

This logistical challenge could be easily solved through a back-up system of self-selected people expecting a standby vaccination call. This system would be accessible staff at a vaccination site, and would allow them to filter only for people who could arrive in the relevant timescale – be that before 5pm, or on 2am on a Sunday morning. The system itself need only be simple. So simple, in fact, that a non-developer like myself was able to hack together a viable tool in about 14 hours (see below). A tool like this could get five people to a spare vial in under two hours. If it could repeat that trick 300 times across England – a trivial amount of scaling for a simple app – then through the grim calculus of COVID, it would unarguably save lives.

The second challenge, however, is getting acceptance to use such a tool. There are surmountable concerns around data protection, and app reliability at scale. For these reasons, it is a considerably better idea to have a backup system that is complete separated from NHS patient records, holds minimal personal data, and is entirely voluntary. But the biggest barrier to acceptance is whether vaccination centres are to be permitted to bypass the prioritization queue if and only if the alternative was vaccine being wasted.

When the alternative is waste, the case against emergency reallocation is morally indefensible.

To be clear, that is the only purpose of this proposed tool: to prevent vaccine from being thrown away. It’s would be a backup system, not a challenge to the primary system, and not a means for anyone to “jump the queue”. Yes, the private gains here are earlier immunity to those who are able to receive last-minute vaccine. These people are likely to be younger, richer, and more tech-savvy than average. It is easier for an office-worker to get 45 minutes off in the middle of the day to be vaccinated than a haulier. Yet these private benefits are only part of the social benefit, which is community immunity, a considerable public good. When the alternative is waste, the case against emergency reallocation is morally indefensible.

The potential for such a secondary system to have an impact is now. The first widely distributed (Pfizer/BioNtech) vaccine appears to be both the most effective, but also the least stable. We can solve this, but a solution that takes weeks to develop will have a much more limited impact. So my suggestion is that we – by which ideally I refer to people with much greater skill than me – can hack together a “minimally viable product” (MVP), which could be trialled in a limited area over a period of days, before a broader rollout.

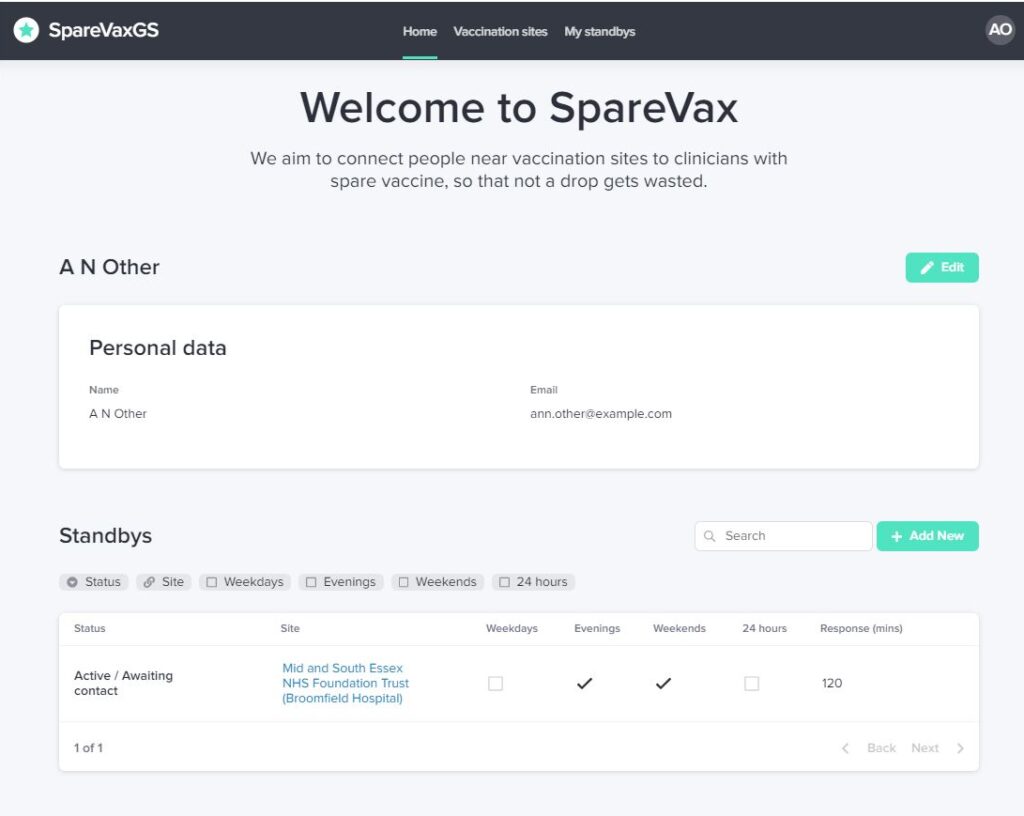

My amateur attempt at such a system is SpareVaxGS. I built it in 14 hours using Stacker, which is an intuitive no-code tool. The potential recipient is able to login (through a verified email account), and browse vaccination sites to find sites near to them. They can then create a “standby” indicating their contact number, availability, and typical response time to be on site.

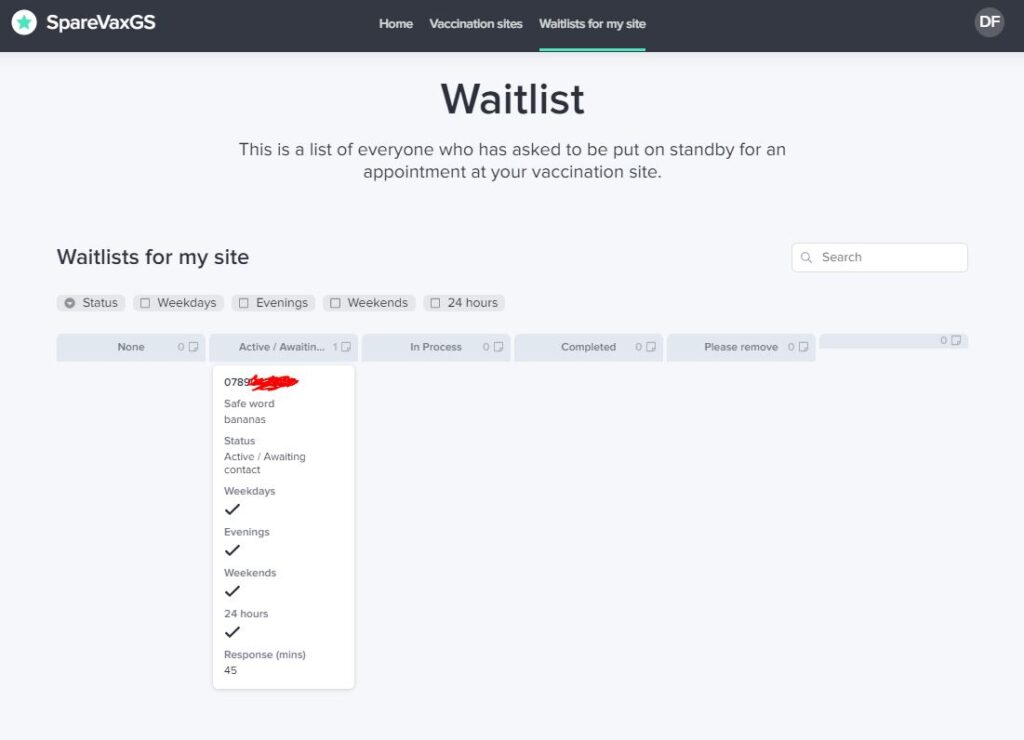

The clinician at a vaccination site sees a kanban-type board, listing the phone numbers of all the people who are ready to drop everything to get an otherwise wasted vaccine. They also see potential recipients’ typical availability: they won’t call at 1am if the “24-hour” box if not ticked. By design, no personal information is passed to the vaccination site: they see only a phone number, an optional safeword (to protect users against scam callers) , and availability. This isn’t just for data protection reasons, but also to avoid any ability for intentional or unintentional discrimination in deciding who to call in.

Backend data is currently stored in Google Sheets, and the platform could scale easily to 5,000 users, at a cost of around £300 per month. This is not adequate scale for rollout: the average Primary Care Trust in England covers 250,000 people. It might, however, be adequate for a town/city trial, and I’d happily fund the platform during that trial, if any health authority is game to try. If it were successful, I would need considerable help – both technically and financially – to re-architect the concept at a scale that could work nationwide.

That’s the pitch. I’d be interested to make contact with anyone who may be able to help. That might be as simple as critiquing the idea: constructive criticism is most welcome. But it’s likely to be most useful either on the technical side (to build a better platform, if and when required), or on the policy side (to discuss with a busy and stressed health trusts whether and how we can trial). And of course, if you’re a large tech player that is looking for a high-impact project to showcase your platform’s ability to solve social problems in double-quick time, the door is wide open. Can you help?